GOING TO MARS

In 2017, for part of the winter, I rented a bungalow in Florida, and my father stayed with me.

My father is a graduate of Amherst and Harvard, a man whose remarkable career touched many lives. And he has Alzheimer’s.

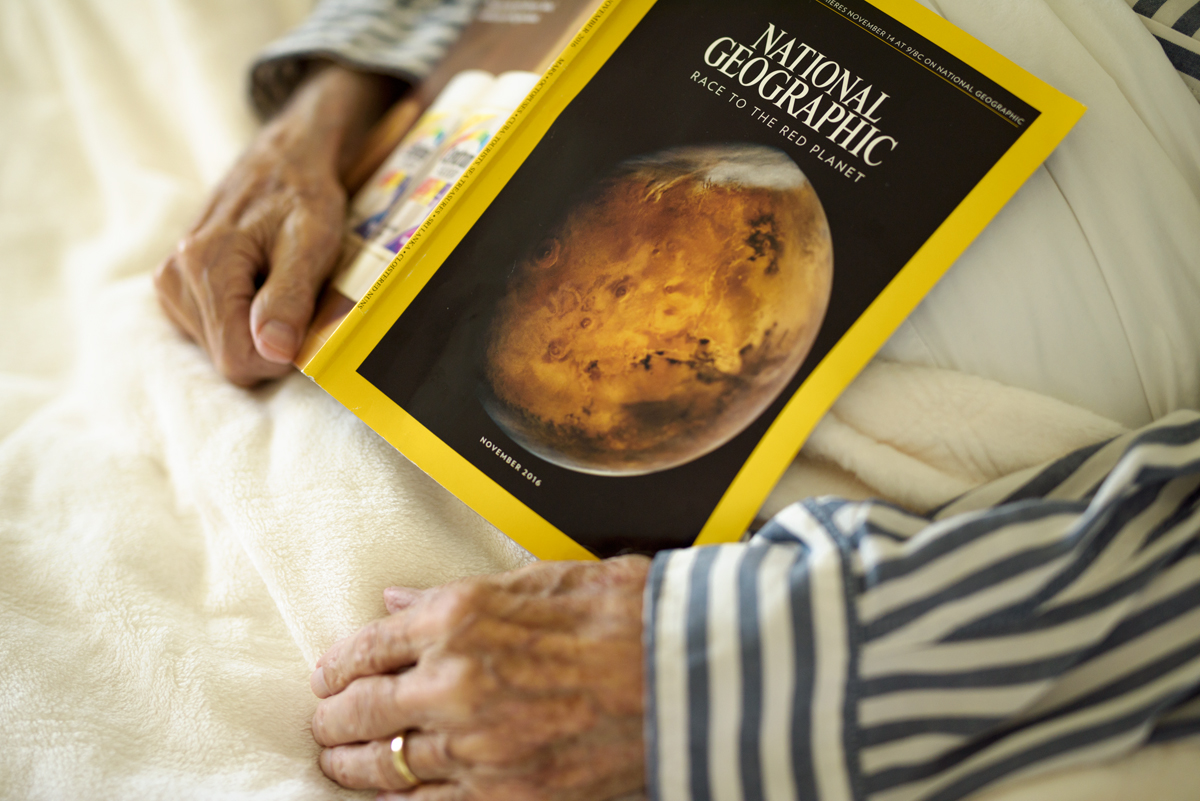

Going to Mars refers to a National Geographic story I read to my father night after night; it is also a personal metaphor for this time I spent with my father.

As I looked after my father, I saw how his mind had changed, like a map being gradually erased. I wanted to know how he navigates the new world around him –- and the alien world inside his head. With my camera, I imagined what it was like to forget, to be confused, to be blank, and yet utterly in the present moment. I also imagined and hoped that this new world contained fragments of wonder and beauty.

(Personal essay follows images)

Have We Gone to Mars?

I am in the doctor’s office with my 89-year old father. I glance down at the file notes. A scribble reads “mild cognitive impairment.”

This is code for Alzheimer’s, which I’ve learned has seven stages, the Reisberg Scale. Dad is in Stage Six.

I’ve read a lot about Alzheimer’s. There is no cure. There are biomarkers for early detection, there are preventative measures, there is medication. But no cure.

I am here to request a new medication that may slow down the brain’s degeneration. Dad is staying with me for a few weeks at a place I’ve rented in Florida, and I am desperate try anything that may delay the dreaded Stage Seven.

As my father works up to the full dosage of the medication, I notice subtle changes. He thinks more logically, and he is more engaged with us – me, my husband, and my aunt and uncle who are visiting. Dad wakes up happy and excited, like a small child on the morning of his birthday, perhaps because he is surrounded by four people who adore him.

We are a family of lively talkers and storytellers, so I've given the household some communication guidelines:

“Please do not ask Dad if he remembers when X, Y or Z happened. He doesn’t.”

“Reminders of memory loss upset him. Instead, tell him the story you remember. Tell it slowly, in the first person. Keep it simple. Try not to use the word remember at all.”

“Dad can still make his own decisions. Ask him if he would like a cup of tea. He will let you know if he wants tea, it just may take a few minutes.”

“Speak slowly and clearly, and do not, under any circumstances, speak to him like a child.”

“We need to let him know he is loved unconditionally. We need to be patient. He is happy when someone he loves is just sitting with him, no conversation necessary.”

Each day, I am more aware of Dad’s need for routine, consistency, patience, and how much more a quiet smile means than a torrent of conversation.

In the mornings, Dad reads a “briefing card,” we've prepared. It reminds him where he is, why he is staying with us, and what is planned for the day. Dad loves these cards; on some subconscious level they connect to his career as an intelligence officer who briefed and debriefed high-ranking government officials, including the President.

Dad delights in watching children play and listening to music. He relishes drinking fresh orange juice each morning. He is rapturous over his bowl of vanilla ice cream and the great full moon rising over the sea-grape trees.

As the days go by, I take photos of my father. Through my lens, I become hyper-conscious of my father’s brain and try to imagine how he now is seeing the world.

I wonder:

Does he connect his delicious breakfast juice with the orange trees growing in the back yard?

He knows the moon is the moon, but he cannot identify his silverware, why is that?

How does he identify objects if he cannot access language?

Are colors more important than shape?

How much does visual context matter?

What distinguishes wonder and awe from bewilderment and fear?

We sing a lot. Dad is fixated on My Fair Lady, and many of the stanzas turn into grand ongoing jokes. “By jove, I think she’s got it” becomes the launch point for a duet, trio or quartet, depending on who is around. My father is very, very happy, and I am too, pushing down the bittersweet feelings of loss, and instead letting our laughter and singing create new strands of connection.

Every night, I read my father a story, the same story, in National Geographic magazine, about the race for Mars, and Elon Musk’s company SpaceX. We usually get to the second page and Dad asks, “Wait. Wait a minute. Emily, have we gone to Mars?”

“No Dad, not yet. We’re working on it. This is a story about going to Mars in the future, probably within the next 25 years.”

Dad shakes his head and says, “Wow, WOW. That’s incredible.”

I think about how Dad no longer remembers bringing home the new television set in 1969, so we could watch the lunar landing.

Astronomy was one of Dad’s passions. He taught my sisters and me to identify the constellations and the most important stars. He also taught us how to run a road race for the win, how to climb up two hundred feet of rock face and rappel down, how to navigate city streets and wilderness.

“Dad,” I say. “We have been to the moon. And we’ve landed a rover on Mars that took pictures and sent them back to NASA. Want to see?”

“Wow, wow, wow, yes,” he says. I turn the page of the National Geographic.

© Emily Hamilton Laux 2024